Translation fraud in the digital age

In the increasingly digitized translation industry, a phenomenon that has so far received little attention is drastically on the rise: organized translation fraud. What sounds harmless is in fact a complex network of forgery, identity theft, and systematic deception – with noticeable consequences for companies that depend on high-quality language services.

Fake translator profiles, stolen CVs, manipulated websites – the methods used by so-called “translation scammers” are professional and well coordinated. In some cases, hundreds of fake identities are created, with the real names and photos of real language professionals, copied references and academic qualifications that have never been acquired in this form. At first glance, the fraudulent profiles appear to be genuine, and in some cases even more convincing than those of genuine specialist translators.

We came across a particularly impressive example in the form of a fraudulent website that purported to be a Finnish translation agency. On closer inspection, however, the visually professionally designed website had numerous linguistic and structural errors – a clear indication of poor quality and a lack of expertise. A glance at the list of fraudsters at translator-scammers.com confirmed the suspicion. Nevertheless, scammers regularly manage to obtain lucrative orders. The consequences: inaccurate translations, project delays, legal risks – and last but not least, considerable damage to the industry’s image.

Translators are also affected

But it is not only clients who fall victim to such machinations. Increasingly, translators themselves are also being targeted. In a particularly perfidious fraud scenario, they receive seemingly legitimate orders for the translation of real, extensive texts. After completing the first part of the project, a payment transaction is finally announced – but on the condition that a sum of money must be transferred to a foreign account for “authentication” or “verification”. The reason sounds plausible at first glance: security precautions or international payment guidelines.

But the real goal is a financial trick: the so-called sunk-cost fallacy is used to psychologically pressure translators into paying the requested amount. The idea is that if they have already invested so much work, it’s only worthwhile if they get paid. After the transfer, however, contact is broken off completely, the fee is never paid and the money invested is irretrievably lost. Time and again, colleagues complain about their misfortune, which shows how deliberately such deception is used today.

As a result, reputable providers such as our translation company ReSartus are facing a growing problem. While we place great emphasis on quality control, transparent processes and reliable specialists, these criminal structures undermine potential customers’ trust in the entire profession. This puts particular pressure on small and medium-sized language service providers, as they have to expend additional resources to protect themselves.

How to recognize a scam

Although the industry is responding with various countermeasures – including watchlists, reporting platforms and publicly accessible databases of fraudulent profiles – the burden remains high. This makes it all the more important to recognize the typical signs of such scams. It is noticeable, for example, that fraudulent applications often come from free e-mail addresses and are sent en masse – usually without reference to a specific project or without a personalized address. Also, suspiciously low prices, unusually fast delivery times and the lack of any web presence or professional references should make you suspicious. Another warning sign is incomplete or contradictory CVs – for example, if years of experience in specialist areas are claimed without specific work samples or clients being provided.

From a technical point of view, many fake profiles can be recognized by the fact that they use copied content, which is often word-for-word identical to other supposed translators on the internet. Plagiarism tools or simple search queries for text passages or profile pictures can help to uncover such duplicates. It is not uncommon for the same information to appear on multiple platforms with only minimal variations. Profiles on freelance platforms should also be carefully checked: a high number of consistently positive ratings in a very short period of time can also be an indication of manipulation.

When choosing a language service provider, it is crucial for clients to choose carefully. Personal contact, clearly defined communication channels, transparent project workflows and a comprehensible quality management system are key criteria for gauging the reliability of a provider. ReSartus, for example, consciously focuses on long-term customer relationships, a clear identity on the internet and individually selected specialist translators – with the aim of clearly distinguishing itself from anonymous, non-transparent mass providers.

In a world where professional deception can be created with a few clicks, a high degree of attention and skepticism is necessary. Because when language becomes a tool, it is not only the result that matters but also the way to get there. And that begins with trust.

Push the Future

Small Businesses and Invoices

Vegan Language – It’s all about the Bratvurst

Accessible Texts – Leichte Sprache from a Translator’s Perspective

Between Deadlines and Diplomacy

Why localization is more than translation

60th Theodor Heuss Prize

The invisible danger: digital translation fraud

Planned revision of the JVEG

Freelancer visa in the UAE

Emigration to Dubai

Cuts and restrictions – Interpreters and Translators in Crisis

Building bridges at the Wilhelm Bock Prize

Funding Programs for Language Mediators in Healthcare

Inclusion in Education: ReSartus Enables International Exchange

The Future of Remote Interpreting – Virtual Conferences

Industry-specific challenges in the translation industry

The Role of AI in the Translation Industry

Hiiios – The video interpreting service by ReSartus

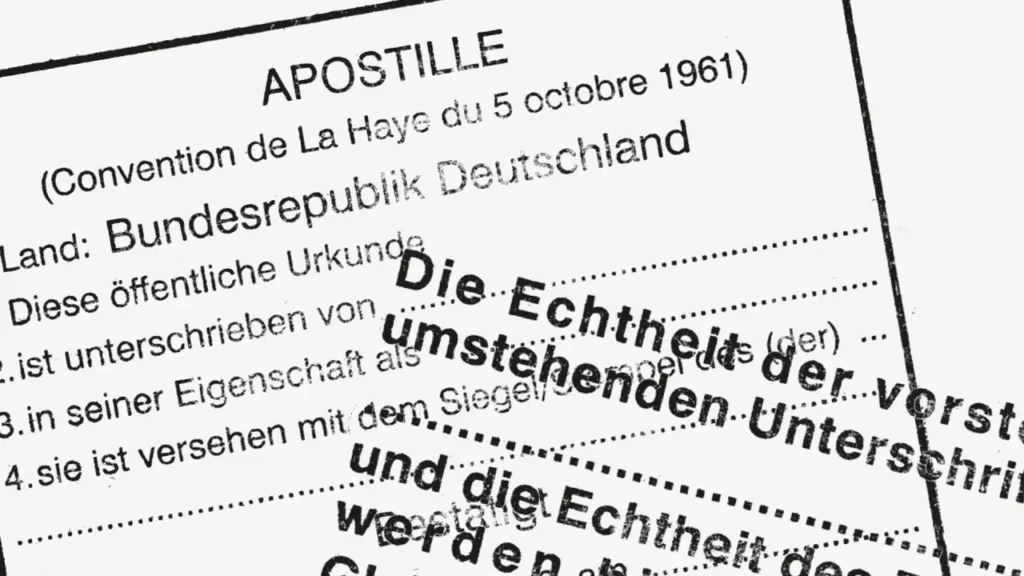

Emigrating from Germany

ReSartus supports the 43rd Erlangen Poetry Festival

Preparations for the COP 28 World Climate Conference

Push the Future

Small Businesses and Invoices